We've been talking to a megolithic corporation about a small job since the Bush Administration.

Recently they admitted they "didn't understand animation" and wanted to know "when they can change things". It would be self-destructive to point out: if you don't "understand" animation, what makes you think you have any grounds to make "changes", so we swallowed our fury and sent along this note, which is helpful to describe the process to potential collaborators who are new to the process.

*Start Note*

In this case, it’ll be closer to Astroboy or Star Blazers –but the idea is the same.

Here are the key steps to the process and what to look for at each point.

Everything stems from this. Any jokes that need tweaking, or characters changed around, or locations altered –this is the place to do it.

There’s always some flexibility with this up until the voice record –which happens before animation begins –but once the track is laid down, any alteration to dialogue involves additional time for talent, audio facilities, voice direction, video edit, and depending on how far into production we are, animators, inbetweeners, trace and painters and compositors.

Character design is a bit like casting for type. The look of the character is defined. At this point we’ll work up several poses of each character.

Since this production is inspired by the classical anime form, that makes this phase much simpler. We know what the general style will be, so from here it’s a question of detail: hair style, clothes, color.

Once we go into production, any changes to design will lead to substantial work. Further, design revisions after this phase invariably compromise the final quality of the picture.

The storyboard will represent the final film in single frame, black and white drawings.

Here we look for narrative continuity, dynamics, general framing and camera position, shot sequencing and visual pacing.

Along with the storyboard, an “animatic” or “leica reel” is created. This is a simple edit of the single drawings against the voice track.

Traditionally, a drawn animation will have a “pencil test” which serves as a full, sort-of, rough cut. The pencil is line drawing of animation, often double-exposed onto a background. It shows the acting performance of an animated character.

Understanding a pencil test is a learned skill. Most people can’t look at one and make intelligent comments without examining the film for a prolonged period.

Pencil tests have come to be a luxury, as drawn animation is difficult to produce on 21st Century budgets.

Nevertheless, we do create motion tests throughout production. Considering the simple nature of this animation style, and the necessity to create much of this work digitally many of these motion tests will be in color.

At this point, it is sort of like a rough cut and “good” take in live action. Some acting changes can be made –along the lines of “is there a better read of that line?”. Different angles, additional shots, and other changes are the equivalent of calling a re-shoot in live action. It’s possible, but just like a re-shoot in live action, it requires a great expense of resources.

By the time the rough cut comes around in animation all the creative decisions have been made. This is a point for fine tuning of edits/transitions/special effects.

What can be done at this point is the same as what you can do in a live action edit when there is no possibility of re-shooting.

Script

Everything stems from this. Any jokes that need tweaking, or characters changed around, or locations altered –this is the place to do it.

There’s always some flexibility with this up until the voice record –which happens before animation begins –but once the track is laid down, any alteration to dialogue involves additional time for talent, audio facilities, voice direction, video edit, and depending on how far into production we are, animators, inbetweeners, trace and painters and compositors.

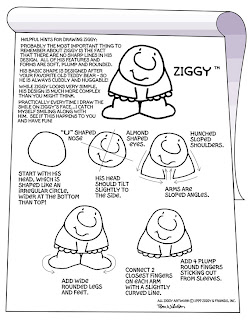

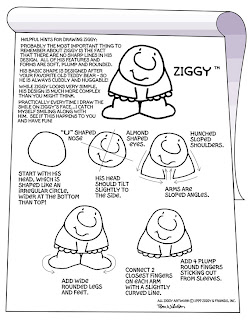

Character Designs

Character design is a bit like casting for type. The look of the character is defined. At this point we’ll work up several poses of each character.

Since this production is inspired by the classical anime form, that makes this phase much simpler. We know what the general style will be, so from here it’s a question of detail: hair style, clothes, color.

Once we go into production, any changes to design will lead to substantial work. Further, design revisions after this phase invariably compromise the final quality of the picture.

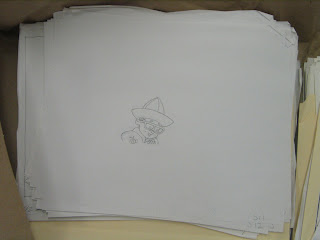

Storyboard

The storyboard will represent the final film in single frame, black and white drawings.

Here we look for narrative continuity, dynamics, general framing and camera position, shot sequencing and visual pacing.

Along with the storyboard, an “animatic” or “leica reel” is created. This is a simple edit of the single drawings against the voice track.

Animation

Traditionally, a drawn animation will have a “pencil test” which serves as a full, sort-of, rough cut. The pencil is line drawing of animation, often double-exposed onto a background. It shows the acting performance of an animated character.

Understanding a pencil test is a learned skill. Most people can’t look at one and make intelligent comments without examining the film for a prolonged period.

Pencil tests have come to be a luxury, as drawn animation is difficult to produce on 21st Century budgets.

Nevertheless, we do create motion tests throughout production. Considering the simple nature of this animation style, and the necessity to create much of this work digitally many of these motion tests will be in color.

At this point, it is sort of like a rough cut and “good” take in live action. Some acting changes can be made –along the lines of “is there a better read of that line?”. Different angles, additional shots, and other changes are the equivalent of calling a re-shoot in live action. It’s possible, but just like a re-shoot in live action, it requires a great expense of resources.

Rough Cut

By the time the rough cut comes around in animation all the creative decisions have been made. This is a point for fine tuning of edits/transitions/special effects.

What can be done at this point is the same as what you can do in a live action edit when there is no possibility of re-shooting.

*End note*

1 comment:

You forgot the part at the end where the client suddenly decides they'd really want the film in HD format...

Post a Comment